Diving

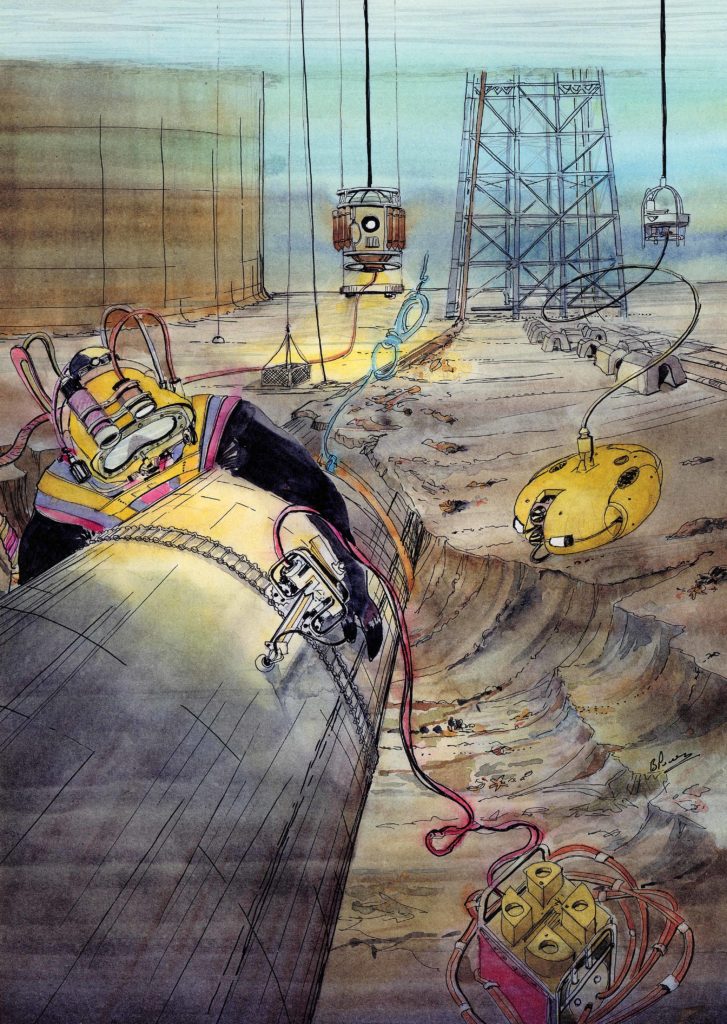

All such work was originally done by divers, but simple remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) began to be used in the late 1970s.

Known as “eyeballs”, the first of these were used for visual inspection and for monitoring divers performing difficult assignments in order to improve their safety.

The ROVs became steadily more sophisticated and took over an increasing amount of subsea work. Most underwater operations today are done without diver assistance.

Divers

Divers have been an integrated part of the Ekofisk workforce ever since trial production began on Gulftide in 1971, where they carried out various assignments.

These included regular inspections of the seabed near the platform’s legs to spot erosion in good time and counter it with the aid of sandbags. Another job was to inspect the riser base plate for erosion.

During the early years, Ekofisk crude was carried to market in shuttle tankers. A regular diving job was to inspect flanges on the flowlines to the loading buoys and to make repairs.

The buoys themselves and their mooring systems also had to be checked, as did the anchoring equipment and loading hoses for the tankers. Hawsers and hoses floated in the sea in order to be retrieved by the tankers when they arrived to load. Almost every time gale-force or stronger winds had been blowing, this equipment was all tangled up and had to be sorted out.

Not infrequently, too, all or part of a loading buoy would have been torn free and had to be restored again as soon as weather and wave heights permitted.

The service vessels in the 1970s were called Imkenturm and Pagenturm, and took it in turns to provide standby on the field. Both were equipped for surface-oriented diving, while the first of them also carried a bell system.

When substantial underwater work had to be done, a dedicated diving team was mobilised to Choctaw 1. This vessel carried its own bell system for deeper jobs.

However, the bulk of subsea assignments were performed as surface-oriented diving which could be used for water depths down to about 72 metres.

When diving support vessel Seaway Falcon arrived in 1975, saturation dives became even more common. Divers here were housed under seabed pressure in a chamber on deck.

They were pressurised to two different levels – 50-58 or 30 metres of water – depending on the work to be done. The diving bell was used for transport to the work site and to provide communication and breathing gas for the divers.

The diving supervisor instructed the men in the water what to do from the control centre. They usually spent about three hours outside the bell to do a job.

One diver always remained on standby in the bell while the other was out working. Once they had completed their time submerged, the bell was hoisted back to the surface.

The men remained in the pressure chamber between each bell run, with food and drink supplied via air locks. Video cameras permitted constant monitoring from the control room.

A saturation diver usually spent up to 16 days at a stretch under pressure. They would undergo decompression during their final 60 hours.

Continuous construction work characterised the first period on Ekofisk. Divers were assigned to conduct exact topographical and geotechnical measurements. Irregularities in the seabed where a platform was to be installed might have to be levelled out. Other jobs included inspection, installation, equipment overhaul and welding.

Where pipelaying was concerned, divers usually carried out route surveys and topographical surveys as well as assisting throughout the operation. Positioning pipelines and using measurement equipment on them were other jobs.

Diving supervisor

The diving supervisor’s role on Ekofisk has changed in line with technological advances in this area. Until the mid-1970s, they also led the diving team on minor operations.

They were the immediate superior of the divers, with management responsibility for all the work done by their team.

While diving was underway, their place was at the controls (in the control room where one existed) where they directed the diver’s work over the communication link and otherwise operated everything relating to life support.

The latter included supplies of air/breathing gas and possible hot water. Depth, time submerged, descent/ascent speeds, decompression stops and so forth were managed in accordance with the diving tables when the diver was in the water, the bell or the pressure chamber.

From the controls, the diving supervisor also managed the activities of the diving support team on the surface – winching, umbilical handling, lowering/retrieving tools and so forth.

In addition, they served as the link between the diver and necessary heavier assistance when this was in use. That included crane operators, for example.

When no dives were being made, they were the team leader for inspection, maintenance and repair of its equipment, and were responsible for purchasing consumables – such as breathing gas and carbon dioxide absorbents – spare parts and so forth.

The supervisor was also responsible for all logging and other paperwork. They took their orders from and reported to their own diving company on administrative and technical matters, and from the contractor where work was concerned.

After specialised support vessels and saturation diving were adopted in the mid-1970s, the size, duration and scope of this work increased.

That made it natural to spread the diving supervisor’s duties between several different people – diving superintendent, camera operator, life support technician (LST), gas technician and so forth.

The basic job of today’s diving supervisor is still to be in communication with the divers and manage their work, lead surface support and act as a link between the diver and direct external assistance.

ROV operator

Phillips was the first operator on the Norwegian continental shelf to adopt remotely operated vehicles, or ROVs, to support underwater work.

Known as “eyeballs”, the first of these were very elementary and served basically as motorised cameras. They were operated from the control room on the surface ship via an umbilical cable.

Diving support vessels (DSVs) used these devices for visual inspection and monitoring of the divers in order to enhance their safety. Subsea operations on Ekofisk utilised two RCV225 eyeballs, one on each of the two DSVs which operated there.

More advanced ROV technology was adopted during the 1989 inspection programme on the field, with work done by two very sophisticated manipulator arms mounted on the vehicle’s front.

It could also carry sonar equipment, up to five underwater cameras for both panoramic and close-up photography, and various modules for jobs such as weld cleaning and anode installation.

Ninety per cent of all subsea inspection on structures and pipelines was conducted by ROV in 1989. But divers were still needed, and a project was launched to combine them with ROV use.

In order to simplify diving conditions, a platform was installed on either side of the ROV for the divers to stand on while they carried out their work.

In addition, a modular framework was developed with pumps and hydraulic connections for tools. This was installed under the ROV, enabling it to carry equipment down to the divers.

Another project was started in collaboration with Elf to develop an ROV able to conduct non-destructive testing (NDT) on steel structures. A dedicated manipulator arm, software and tools were produced for this purpose.

As a discipline, operating underwater activities remotely from surface control stations covers a number of different work areas using ROVs and remotely operated tools (ROTs). Operations, maintenance and repair are carried out on subsea installations and process facilities.

Such work is pursued particularly in the offshore petroleum sector on continental shelf areas around the world, and embraces the exploration, development, production and cessation phases.

However, the technology is being increasingly extended to other contexts and will be utilised to a greater extent in the future for aquaculture, for example.

Further potential areas of application include environmental mapping, work on military equipment, cleaning up environmentally hazardous waste and in hydropower generation.

Interesting analysis! It’s amazing how patterns emerge even in seemingly random events. Sometimes a quick mental break is all you need – I’ve been enjoying a bit of solitaire bliss lately to unwind! Great post.

Yo, trying to find a spot to win? win55club is calling your name. Lots of chances to score some wins. Check it out at win55club and see if today’s your lucky day!

If you’re into slots, gotta check out v888slot! They’ve got a ton of different games and it’s easy to get started. Head over to v888slot.

Looking for a solid online casino? v888casino is pretty decent. I’ve had some good times there playing the different games. Give v888casino a try!