Alexander L Kielland – Norway’s worst-ever industrial accident

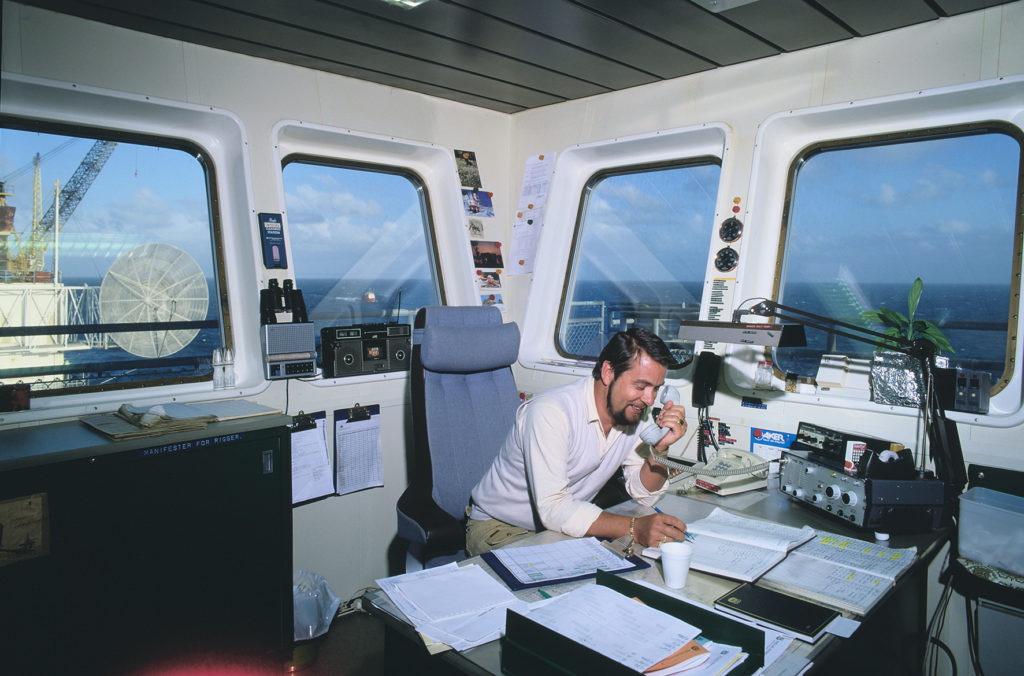

Unable to believe his ears, Fanebust stopped to listen but heard no more. He was soon in contact with supply ship Normand Engineer, which lay two nautical miles north of the flotel. It had also picked up the Mayday call and wanted to sail immediately to investigate. Normand Skipper was ordered to do the same.

The rescue operation was difficult. Night was falling and a gale blowing. In just 20 minutes, the inconceivable had occurred – fatigue failure in a bracing had caused one of the flotel’s five legs to tear off. The unbalanced unit then tipped over. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Kvendseth, Stig S, Giant Discovery. A History of Ekofisk Through the First 20 Years, 1988: 144-145.

Chaos prevailed on board as the list became more and more pronounced. Much went wrong with lowering the lifeboats. Many of those on board had no chance, and 123 people died. Just 89 survived the worst industrial accident in Norwegian history.

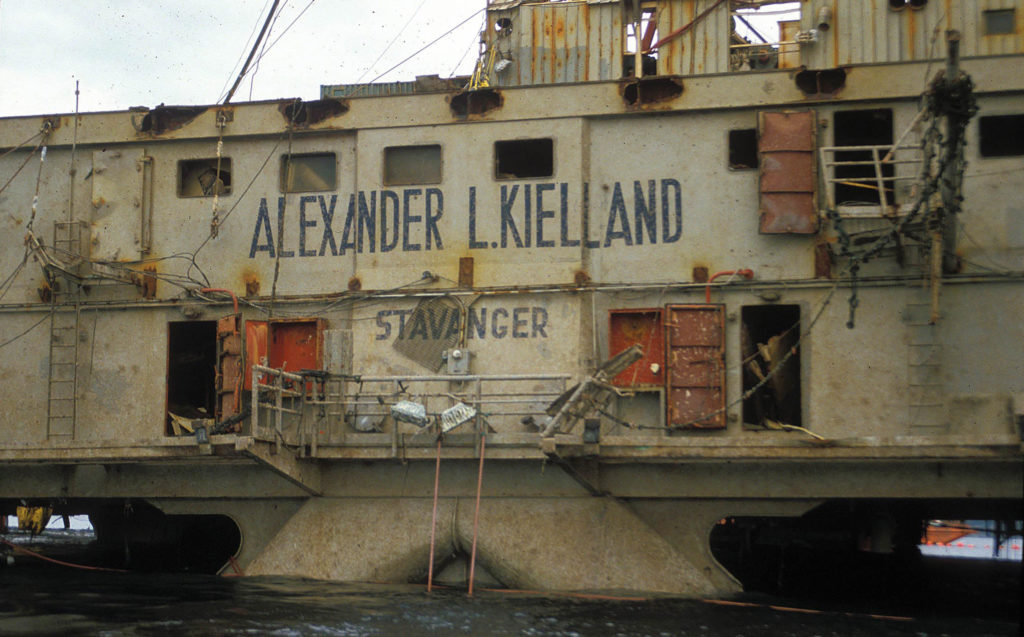

The wreck

Named for a well-known 19th century Stavanger novelist, Alexander L Kielland had originally been commissioned as a drilling rig by the Stavanger Drilling company. It was built to the French Pentagone design at France’s Companie Francaise d’Entreprises Metalliques (CFEM) yard in 1976.

On Greater Ekofisk, the rig was used solely as a flotel and had been moored from the summer of 1979 alongside the Edda platform, a few kilometres south-west of the Ekofisk Complex.

It was linked to Edda by a bridge, but this had been removed on the day of the accident because of the bad weather.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ryggvik, Helge and Smith-Solbakken, Marie, Blod, svette og olje, Norsk oljehistorie volume 3, Oslo, 1997: 213.

The loss of one support column meant the flotel began to list. That in turn caused water to pour into the other four pontoons and into the topside decks, increasing the incline even more.

People on board strove despairingly to reach the lifeboat deck. Very few managed to collect a lifejacket from their cabin. The supply of survival suits was limited. Stocks of lifejackets around the public areas were soon exhausted.

A number of unfortunate circumstances combined to complicate evacuation. Three of the seven 50-seater lifeboats were crushed against the flotel side by the list. Only two of the remainder were used.

Those on board had received inadequate safety training, which was not mandatory for ”hotel guests” under the prevailing regulations. Most were therefore unfamiliar with the safety equipment.

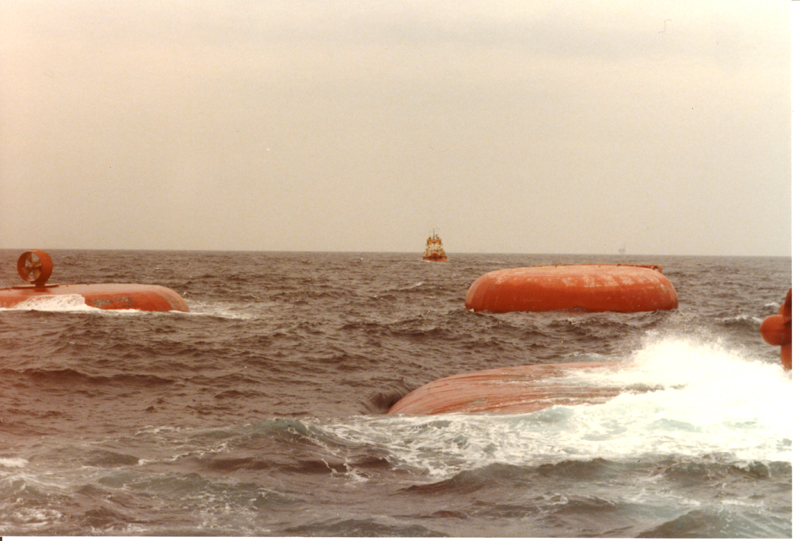

Nobody was able to work the release mechanism on the inflatable rafts, which had a capacity of 400 people. A couple of them nevertheless released themselves when the rig capsized, and three men got into of them. Another 13 managed to swim across to rafts thrown from the Edda platform.

Fourteen of the people who landed directly in the icy sea were saved. Seven managed to swim to the platform and were hoisted up in personnel baskets.

The remaining survivors had succeeded in entering lifeboats and were rescued by ships or helicopters. They reported very dramatic experiences.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Smith-Solbakken, Marie, Historien om plattformen som ikke kunne velte. I: “Alexander L. Kielland” – ulykken: Ringene i vannet. 2017, Hertervig Akademisk.

Rescue work

Several factors hampered rescue efforts. Darkness fell quickly, and fog thickened. The south-westerly wind created wave heights of six-eight metres, combined with a strong current. Temperatures were 7°C in the air and only 4°C in the sea.

So only the vessels which arrived first at the accident site had any realistic chance of rescuing survivors from the sea and from rafts.

The joint rescue coordination centre (JRCC) for southern Norway was alerted within minutes of the disaster, and an extensive rescue campaign was launched at once.

This involved aircraft, helicopters from Norway, Denmark, West Germany and the UK, and naval and civilian vessels from the whole North Sea basin.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar and Gjerde, Kristin Øye, Uglandrederiene. Verdensvirksomhet med lokale røtter. 1996: 378-379

Divers were mobilised in the days after the accident to do the demanding job of finding the dead and bringing them to the surface. This had to done under the capsized flotel with masses of wreckage washing around.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, Kristin Øye and Ryggvik, Helge, On the Edge, Under Water. Offshore Diving in Norway, 2014.

What caused the accident?

The commission of inquiry into the Alexander L Kielland accident submitted its findings on 6 April 1981. On 2 April 1982, the Ministry of Local Government and Labour followed up with a White Paper.

In Norwegian Official Reports (NOU) no 11 1981, the commission concluded that the accident was caused by a fatigue crack in one of the braces which held the flotel’s support columns together. This fracture occurred in a small weld holding a flange plate which supported a hydrophone – a sonar device used during drilling operations. Once the brace had parted, progressive failure of the other bracing led to the loss of the D support column. That left the flotel unbalanced and it began listing. In turn, that meant the pontoons at the base of the columns and the deck began to take on water, and the whole structure turned turtle within 20 minutes.

The commission found a number of faults, including poor inspection routines and safety training. A standby ship should have been no more than 20-25 minutes from the flotel. Technical weaknesses in rescue equipment were also criticised.

New safety measures

Immediately after the accident, the Norwegian Maritime Directorate demanded that all floating units off Norway should be taken to land as soon as possible and checked for cracks.

Regulations were introduced which required that such floaters must remain buoyant even it one of its support columns came off – by making parts of the deck structure buoyant, for example.

In the autumn of 1980, the directorate required that all personnel on both fixed and floating units be issued with survival suits. That is perhaps the most visible outcome of the accident.

Inquiry and righting

- 28 March 1980 – the government appoints a commission of inquiry into the Alexander L Kielland accident headed by district judge Thor Næsheim from Sandnes south of Stavanger.

- 20 April 1980 – the flotel wreck is towed in from the field and moored in the Åmøy Fjord just north of Stavanger for more detailed investigation.

- 7 August 1980 – Sweden’s Nicoverken and Structural Dynamics in the UK are commissioned to turn the unit right side up.

- Late August 1980 – the wreck is towed to the Gands Fjord off Stavanger, where plans call for the righting operation to take place.

- 27 October 1980 – the righting attempt is launched under the direction of Scott Cobus.

- 12 November 1980 – work has to be halted for technical reasons.

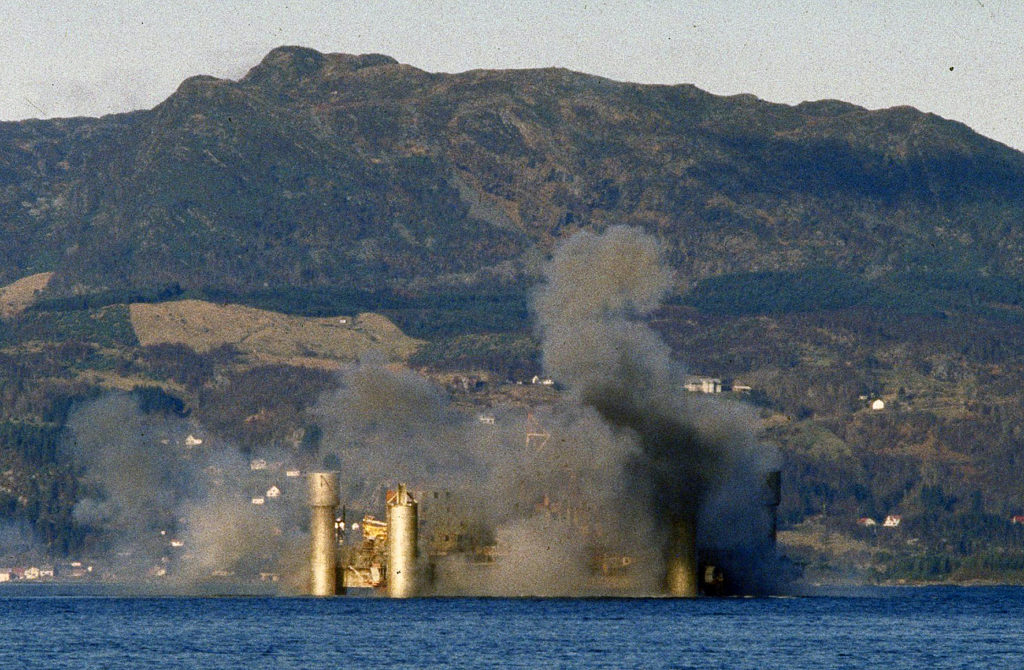

- September 1983 – After several attempts, the flotel was finally righted . Following more detailed investigations, it was finally scuttled in 700 metres of water in the Nedstrand Fjord north of Stavanger.

Witnessed rescue operation from land

Lars B Takla was a chief engineer with Phillips when the Kielland accident occurred. He reports that one of his jobs was to participate in a sub-committee for emergency preparedness in a sort of forerunner to today’s Norwegian Oil and Gas Association.

We had divided the North Sea into sectors, and this was a ’sector club’ where we collaborated across national boundaries. Ekofisk lay in the green sector, which was also responsible for Denmark and possible emergency response equipment there as well as in Germany, the southern UK and Norway.

Arne Holhjem worked with me to draw up this sector-club plan. We compiled an overview of all platforms and all standby ships to have to hand. As green sector coordinator, I was closely involved in the Kielland accident by mobilising equipment and help, and so forth.

Kielland was, of course, a floating hotel converted from a drilling rig. Demand for personnel in the area was very high while we were pursuing all these parallel developments. We had 4-5 000 people on the pipelay barges alone, so there were a huge number out there.

We’d also placed a new accommodation module on Henrik Ibsen, Kielland’s sister rig. Both these units were built for drilling, of course, but demand for such work was not that high at the time while a crying need existed for accommodation – which is why the rigs were converted to flotels.

While Kielland was already offshore, Henrik Ibsen was sent up to Stord [south of Bergen] to be fitted with a modern purpose-built hotel. This was the first of its kind in the North Sea and, for that matter, the world.

It was then made available for viewing in the harbour at Risavika [outside Stavanger]. We had allowed people to bring their families and take a look. I was out there with my wife and our two boys, and dinner was served to all the visitors after a tour.

We sat with Svein-Erik Bjørkelund, who was information manager in Phillips and responsible for all media contact. I knew him after a couple of joint visits to Teesside. While we sat there and ate, he was called over the loudspeaker and told to go to the radio shack.

He rushed out. When he returned, he said: ’I think we must go ashore at once. Something serious has happened’. I asked what this was, and he replied: ’I’m not sure, but I think it’s something terrible’.

Accompanied by my whole family, we boarded a supply ship which was shuttling back and forth between rig and harbour. My family returned home, and I went to the emergency response room at head office which was already in full swing. When we got there, 15-20 minutes or thereabouts had already passed.

On a noticeboard where messages were posted as soon as they came in, I saw it stood: ’Alexander L Kielland tilted over, 18.30’. I knew the weather was bad out there, and thought: ’Dear God, nobody’s going to be able to survive this’.

I spent about the next two days there before taking a break and going home. It’s clear that having been involved in something like this leaves a mark on you. You become conscious that such things must be avoided at all costs.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lars A Takla interviewed by Kristin Øye Gjerde, 19 December 2002.