Eyewitness to the 1969 discovery

He still has a brandy bottle at home full of the first oil to come up, along with his own unique photographs and films shot during the pioneering years of Norwegian oil history. This collection even includes a photograph from the Cod discovery in 1968, although he was not working on Ocean Viking at the time. Read on to learn how that came to pass.

From tanker to supply ship

A series of coincidences led to Munkejord’s presence on the rig when the first commercial discovery was made on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS).

Born in Stavanger on 30 April 1941, he was determined to go to sea from an early age and secured a job at the age of 15 in the galley on the Langfonn cargo ship owned by Sigval Bergesen. After a couple of years, he trained as a ship’s cook in Haugesund north of Stavanger and continued to serve on several ships with the same owner. That took him around the world.

Munkejord eventually married and had children, which meant life at sea became less attractive. He wanted more time at home and tried to find work ashore. But times were hard and jobs scarce, so he was pleased to be taken on by British supply ship Kent Shore. That gave him greater opportunities to be with his family.

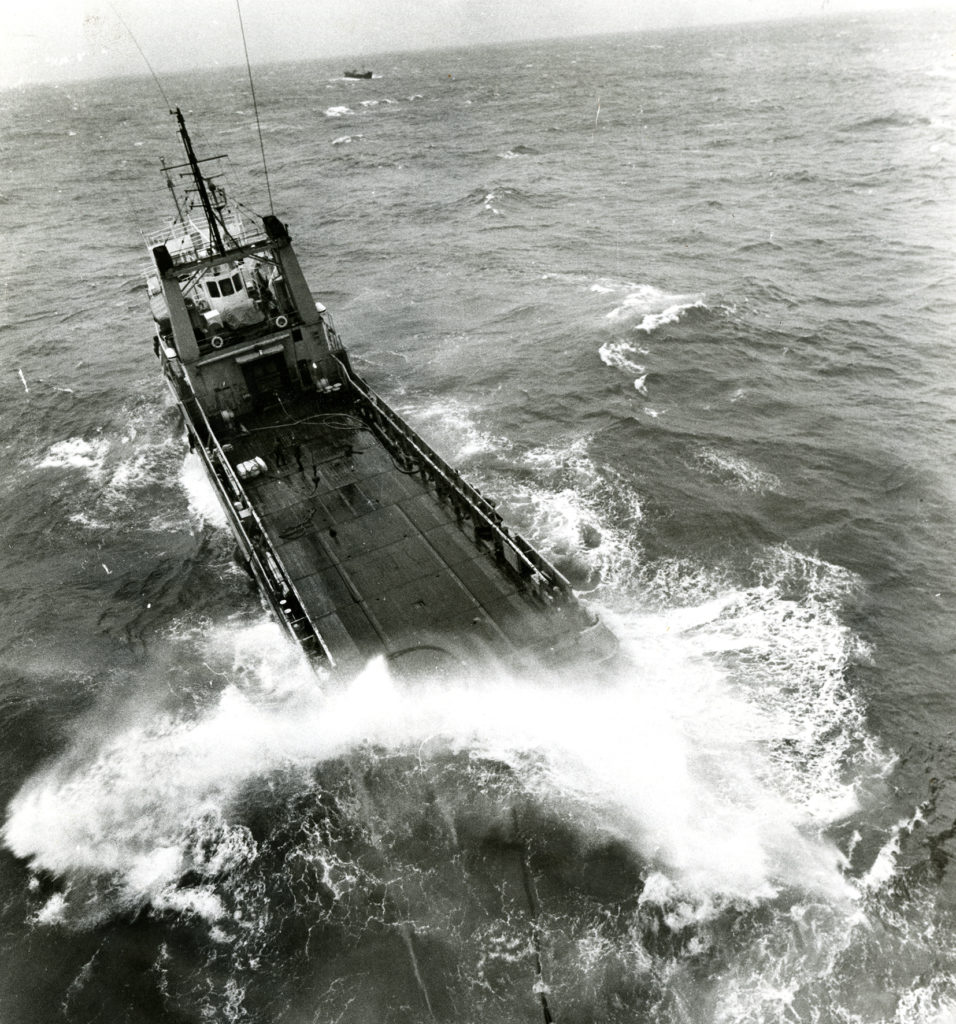

Kent Shore supplied drilling rigs with everything they needed. Working there was no Sunday school. The winter weather could be extremely rough, with 20-metre-high waves.

Being alongside a drilling rig was impossible in such weather. The sea had to be relatively calm when the little ship lay under the rig to load and discharge.

In June 1968, the Kent Shore crew witnessed a rather special event and Munkejord took out both still and movie cameras to capture the moment. Their ship was lying close to the Ocean Traveler rig, where a gas flame 15-20 metres long was blazing above the derrick.

A helicopter was due to land, and the Americans were said to be burning off gas to get the fog to lift. But the flare actually showed that gas had been found in Cod. The photograph soon graced the front page of local daily Stavanger Aftenblad – something Phillips was not particularly pleased about. Ocean Traveler personnel were questioned in a bid to establish who had taken the shot and sold it to the press, but nobody owned up. It did not occur to anyone that the photographer might have been on a supply ship.

An accident occurred on Kent Shore later that year when it was lying alongside Ocean Viking. Its propeller ran for more than 10 hours, things overheated and a cabin began to burn.

Although the vessel was a complete write-off, nobody on board was hurt. They were lifted on board the rig and took several days to get ashore, dirty and dishevelled, on Kent Shore’s sister ship. With no opportunity to change clothes, their underpants became more and more rancid.

To Ocean Viking

What was Munkejord to do after his workplace had been consumed by fire? He took a casual job on the quay at the Strømsteinen offshore base in Stavanger.

The foreman there turned up one day and said that three men were needed right away on Ocean Viking. Munkejord asked for how long, but got no answer. After objecting that he had no clothes, the foreman asked if he wanted the job or not. “I’ll go if you call my wife,” answered Munkejord and became one of the trio. But the foreman forgot to call, and his wife undoubtedly wondered what had become of her husband when he failed to return home for the next four days.

Once back in Stavanger, Munkejord went to Odeco’s office in the Anker Building to ask if it had more work for him. In the corridor, he ran into one of the bosses he had met offshore. Summoning up his courage, he asked: “Bud, do you have a job for me?” Bud responded: “Haven’t I seen you before? I fired a guy a few days ago.” Although Munkejord thought working as a roughneck on the drill floor would be tough, he accepted the offer and flew offshore a couple of days later. He spoke English, was young and fit, and gradually got used to the hectic pace on board. Working seven days on the rig with the next seven off was great.

A roughneck on Ocean Viking had a variety of duties. Norwegians did the heavy work, while the Americans held the supervisory jobs.

Where Munkejord was concerned, he toiled up in derrick, broke out and made up drill pipe, did maintenance, and kept the drilling process going.

The crew worked pretty fast, he says. “We managed a round trip – pulling out the drill string from 8-10 000 feet, replacing the bit and running in again – in the space of a shift. “We took about a minute to break each pipe joint. It was a bit of a competition as well. We ranked among the best in the world in terms of the time taken.” The work could be physically demanding, with the tongs used to grip the drill string weighing about 100 kilograms. Despite the manual labour, with rotating pipe and the spinning chains, virtually no accidents happened on Munkejord’s shift.

But it must be said that two divers and a roustabout (deck worker) who was hit on the head by an object died during the years he worked on the rig, from the autumn of 1968 to 1972.

Accommodation was normally in four-bed cabins. The gang he worked with on his shift became well integrated. After 12 hours at work, his body – and particularly his arms – were really tired. The routine then was to get washed, eat and watch a film – which was usually a good way to fall asleep. But working the night shift was tough, because of the difficulty of sleeping and getting the necessary rest.

Ocean Viking also drilled for Elf, without finding much more than salt. This was when the hope of finding commercial oil resources on NCS had begun to dwindle. Several oil companies were preparing to pull out in 1969. As the Odeco workforce knew, that included Phillips. They might soon have to find another job again – perhaps back to shipping.

Last well for Phillips

It is well known that Phillips was committed to drilling a final well in 1969 under the terms of its licence. Failure to do so would incur a USD 1 million penalty from the Norwegian government.

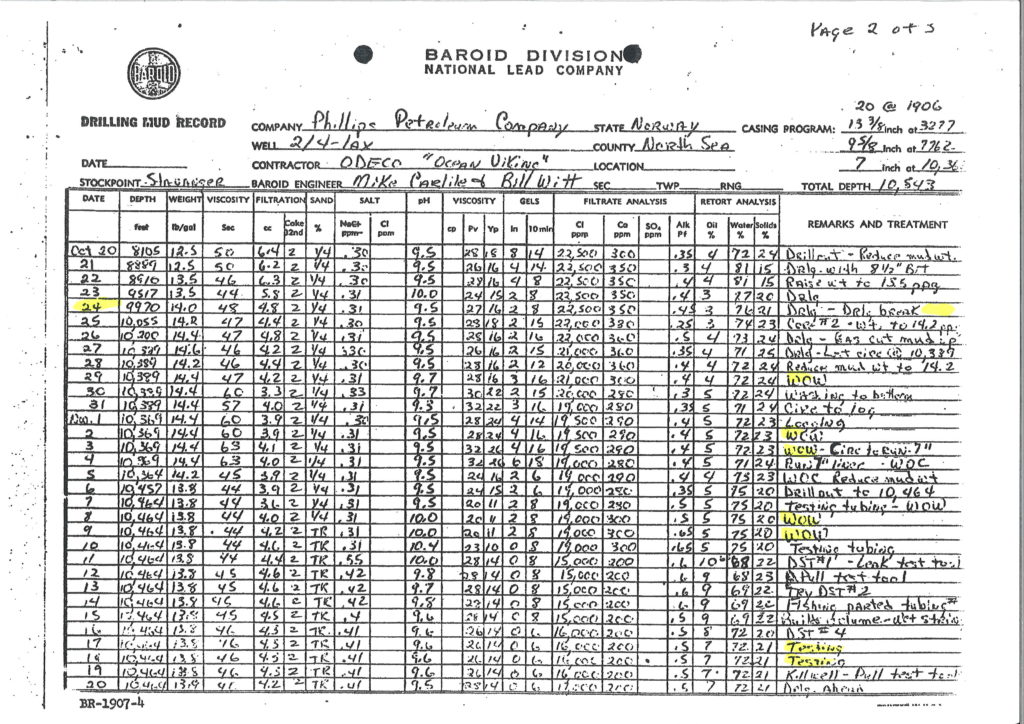

Since the company still had Ocean Viking on charter, and nobody else was interested in taking it over, Phillips decided it might as well drill this last well – designated 2/4-1.

The Norwegian lads working on the rig had little idea about any of this at the time. They spudded the well in August 1969, and experienced a gas kick at 5 000 feet after nine days. Munkejord filmed the sea boiling with escaped hydrocarbons. An underwater camera revealed that a leak existed between two lengths of casing used to line the well. “We had to set a cement plug in the middle casing and install a safety valve before pumping mud down between the two tubes to halt the blowout,” Munkejord recalls. “We then resumed drilling.”

But he suddenly saw that the drilling mud had ceased to circulate back to the rig. He reported this to driller Dick Berg, who took a little time to get this up on his instruments. Munkejord went up to the drill floor to report that there was no mud return. Then the pumps stopped. They had never experienced this before.

In order to test how far down it was to the mud in the annulus between the two casing strings, somebody came up with the idea of dropping a quantity of grease down. But no sound was received that anything had been encountered, so they were not much the wiser. The well was then shut in and pressure began to build.

Trying out various types of mud to balance the pressure so that drilling could resume was a fairly lengthy process, which extended over several weeks. These fluids were light blends which included walnut shells as well as heavy mixtures of bentonite and barytes. The supply ships shuttled back and forth with alternatives and sealing materials. But nothing helped. “If we raised the mud weight, it vanished down the hole,” recalls Munkejord. “If we lightened it, the fluid came back to the deck. We never got things under control.” In the end, all they could do was abandon the well, which was plugged. Munkejord was not involved in the whole business because of the seven-day work schedule, but he heard about it from others.

A little oil also came up during this process, which was taken to the Phillips head office on land. Members of the rig crew secured drops of this crude, which they took home in such glass containers as were available. Munkejord’s share was in a brandy bottle, while another colleague filled a jar which originally held maple syrup – now on display in the Norwegian Petroleum Museum.

First commercial discovery

The results from this “final” well were so encouraging that the Phillips management resolved to resume drilling about a kilometre from the first attempt. This well was designated 2/4-1 AX.

Drilling began, and Munkejord remembers that tension rose as the bit approached the 5 000-foot depth where a blowout had occurred in the previous well. “But nothing happened,” he says. “Perhaps they’d encounter something a little deeper? But no, not there either. So maybe this would be the last well after all.” He was not alone in having such doubts.

But drilling continued, and the breakthrough came at around 9 700 feet. According to the well log, it happened on 24 October.

A bit rotates more quickly when it hits oil-bearing rocks. “Things got a little exciting then,” says Munkejord. “But it was probably the Yanks who understood this best. “We didn’t comprehend so much about what was going on. I think that’s when we cored. And then we carried out a test – in other words, flared off gas.”

The 25 October is regarded as the date of the actual Ekofisk discovery. The geologists then knew they had struck oil in commercial quantities.

Storm damage

Then a ferocious storm hit, Munkejord relates. “It lasted for two days and broke about five mooring lines. The first to go was line two.

“The rig then moved so much that we couldn’t release the mud riser. It broke off at the seabed. There wasn’t anything we could do about that.

“Lines three and four then parted, which caused the mud riser attachments to fracture – blocks which weighed several tonnes. One got wedged under the cellar deck, and the other went into the sea.

“A steel wire cable measuring about four-five centimetres in diameter parted with a terrific bang. And some hydraulic control lines for the BOP broke. One of the drums for these hoses, which stood about three metres high, also fell overboard.”

Munkejord admits that people were a bit worried that, if another mooring line parted, it would end up under a pontoon and overturn the rig with 500 tonnes of drill pipe in the derrick. “Fortunately, however, everything went very well – even though the waves were perhaps 25 metres high and were washing over the cellar deck, and a lifeboat was torn a bit loose. “An unusual mood prevailed. We didn’t like what was happening,” Munkejord admits. But he cannot remember feeling particularly afraid.

After a week and a half, Ocean Viking was back on the well and managed to run tests. The first of these flowed about 16 000 barrels a day, and Munkejord found it a fine sight.

He filmed the flare burning and the black smoke billowing up, and took a photograph of himself and various colleagues in front of the flames from the first Ekofisk test. “The whole rig roared,” he says. “It was quite fantastic. The paint melted. We used all available fire hoses to cool things down. But everything went well.”

They later tried with two flares, and production then doubled – in other words, twice the amount the rig had permission to burn off. Relating this, Munkejord produces a photo he took himself.

He continued to work on Ocean Viking until 1972, and then switched to the Smedvig-owned rig West Venture. But that is another story.

The discovery which changed NorwayWhere does the Ekofisk name come from?